Let me tell you a little story about my wife and me.

At the time that this story took place, we’d been married for more than a decade. For a good chunk of that, I’d been writing a New York Times column about money and feelings. I was also a Certified Financial Planner.

Keep that context in mind as I tell you this story.

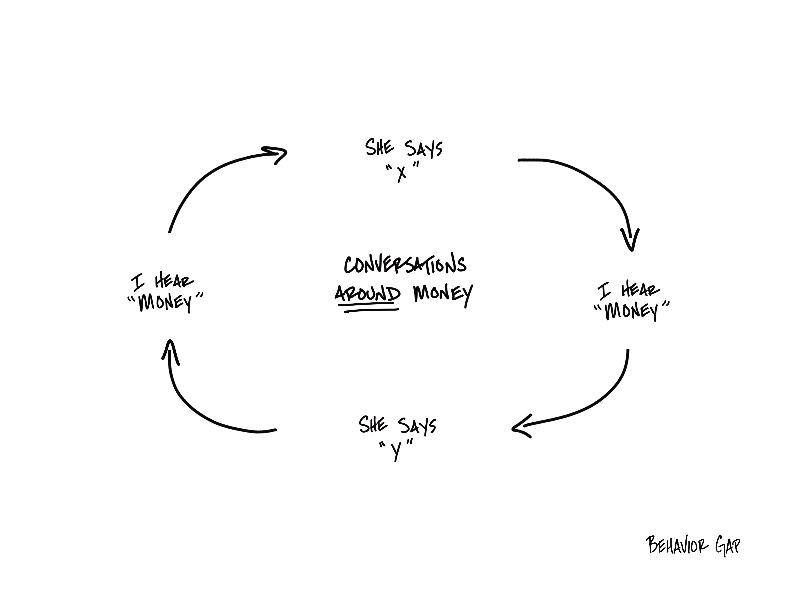

I had been traveling for a few days for work. I came home, sat down, and after my wife and I exchanged normal greetings, one of the very first things out of her mouth was, “Hey Carl, Kate remodeled her kitchen, and boy, it looks great!”

Now let’s pause real quick. Just ask yourself… what did you hear?

Because what I heard was: “Hey Carl, Kate remodeled her kitchen, and boy, it looks great… AND THE REASON I’M TELLING YOU THIS IS BECAUSE I WANT TO REMODEL OUR KITCHEN.”

I immediately stopped listening, and went into calculation mode. Approximately $49,672… at 6% interest… And so, I replied with the only possible rational response: “Cori, we can’t afford that.”

To which my wife replied, “What are you talking about?”

You can probably guess how the rest of the conversation went.

“You said you wanted to remodel the kitchen.”

“No, I didn’t. I said Kate…”

“Yeah, I know… but that means you…”

“No, it doesn’t. It means you’ve been gone for four days, and this was just me trying to start a conversation, which, by the way, is now over.”

…

Look, let me be super clear, this has nothing to do with gender. This isn’t me saying women spend money and men try to save it. There may be some differences in how men and women think about money, but if there are, I’m not privy to that information. This is just a specific example where my wife was saying something, and I was the calculator. Often the role is reversed, and my wife is the calculator.

The point here is that this conversation helped me realize that for 12 years, my wife and I were talking around money instead of about it.

This is just one example out of countless ones from my own life, and that readers have shared with me.

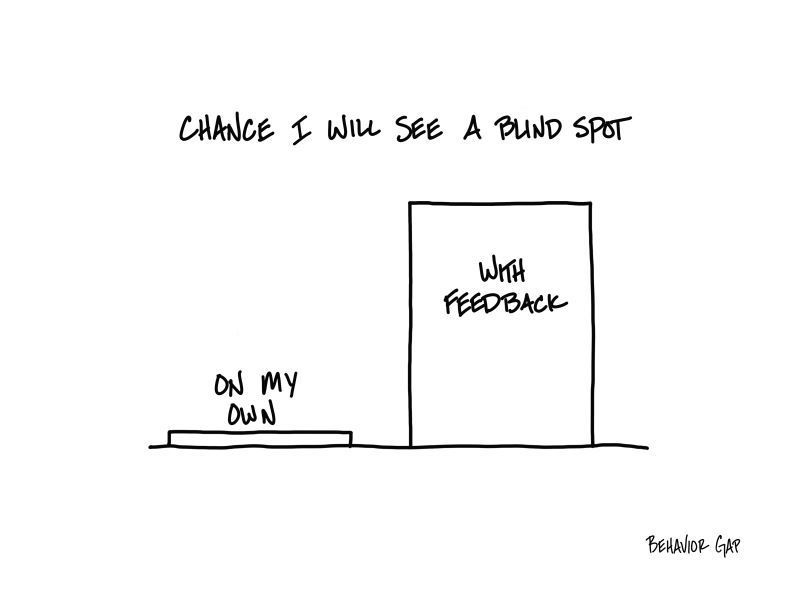

I think the reason we do this, the reason we talk around money instead of about it, is twofold.

1- Nobody taught us how to do it.

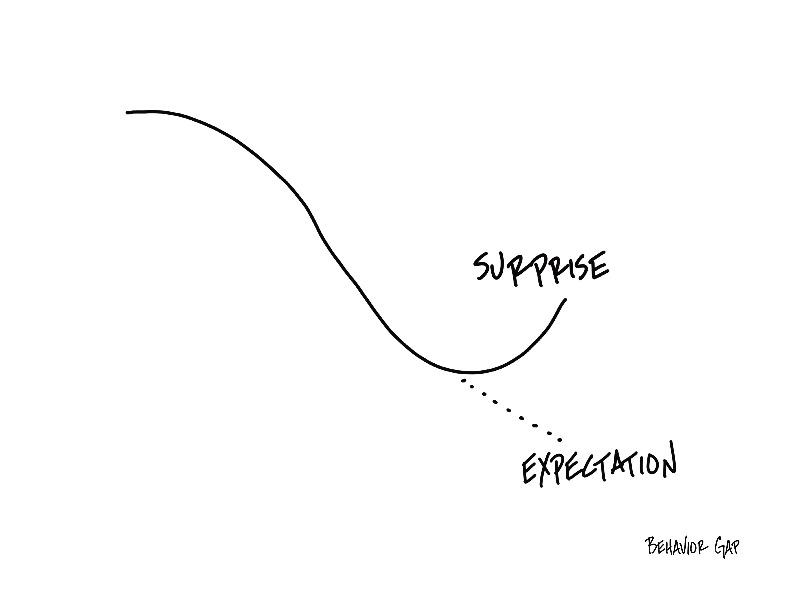

2- When we go to talk about money, it’s suddenly very emotional. We expect it to be rational, but it quickly ends up in the realm of feelings, and we say, “I’m never going to do that again.”

What I try to do now instead (and this is still a challenge for me), is this:

1- Ask questions. “Oh, that’s interesting. Can you tell me more about that?”

2- Clarify the conversation. “Are we talking about buying something, or are we just talking about something?”

3- Don’t calculate… Listen. This may be the most obvious one, but trust me, that doesn’t necessarily mean easiest.

Like I said, it’s a work in progress for me, too. So if you have any suggestions, feel free to send them my way!

What has worked for you?

-Carl

P.S. As always, if you want to use this sketch, you can buy it here.