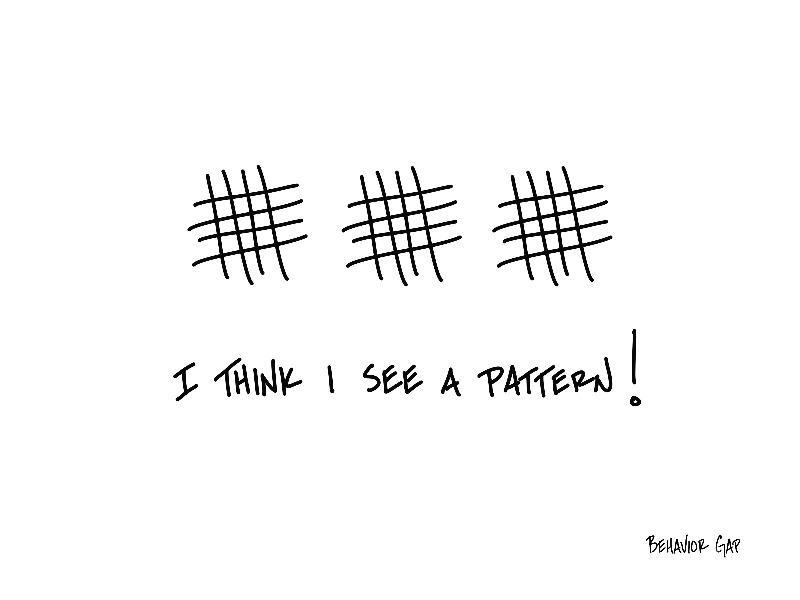

We’re so good at recognizing patterns that we often see them where they don’t even exist.

One of my favorite examples of this is some research done by David J. Leinweber at Caltech. Apparently, he figured out how to predict the stock market using just three variables:

1- Butter production in the United States and Bangladesh.

2- Sheep populations in the United States and Bangladesh.

3- Cheese production in the United States.

Amazing! Right?

It turns out these three variables predicted 99% of the stock market’s movement!

#TimeToStartAHedgeFund.

Just one problem: The joke’s on us.

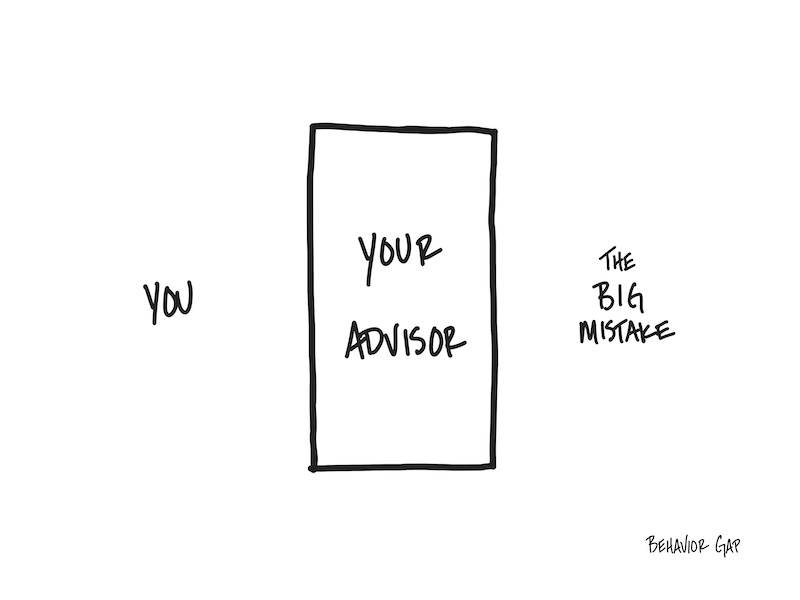

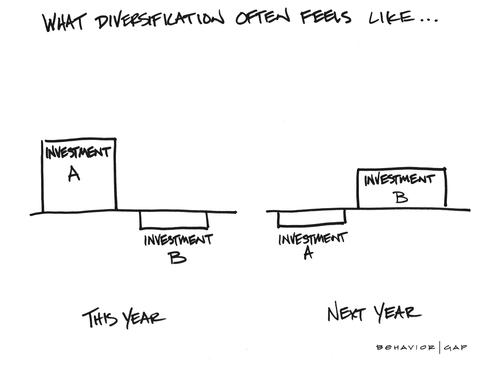

While well-intentioned, the constant pursuit of patterns is one of the big behavioral mistakes we make time and again. We look for patterns. And guess what, they absolutely exist. Right up until you try to invest your money based on the pattern. Then *Poof!* They vanish into thin air.

We think if something happened a certain way in the past, then it will surely continue into the future. We start to believe—we desperately want to believe—that this pattern will have predictive value.

But it doesn’t. And that’s the thing about most patterns—they don’t predict the future, they just describe the past.

While some of these silly data mining tricks might be interesting to talk about, they don’t actually help us.

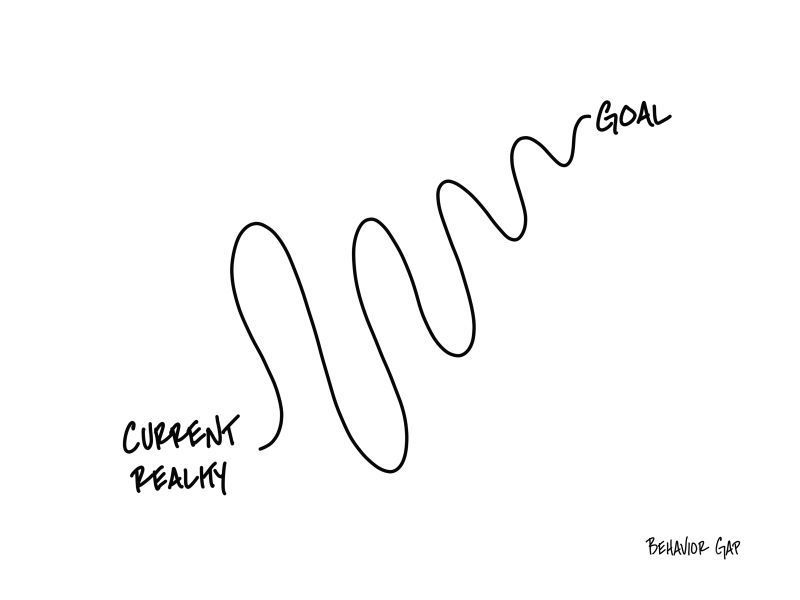

Turns out the only thing that does help when it comes to investing success is good behavior. Day in, day out, year after year.

Now that’s a pattern I can endorse.

-Carl

P.S. As always, if you want to use this sketch, you can buy it here.