Let me tell you a little story about an entrepreneur named Bob.

Bob’s Grandpa started a cookie company. There were a few times when the business almost failed and a few breaks (which Grandpa always said were pure luck), but Grandpa worked his tail off, and the company survived.

Bob’s Dad starts out at the bottom of the business. But he works hard, sticks with it, and makes his way to the top. Now, the business is thriving.

One day, Bob starts working at the cookie company. He doesn’t have much work ethic, but eventually, Dad gets old and retires, and Bob takes over. A year later, Bob sells the company for more than $10M.

Now Bob drives a Tesla with “DSRUPTR” on the license plate and talks about entrepreneurship (he’s a #publicspeaker, of course), as if all you have to do is plug some numbers into a formula and be really smart.

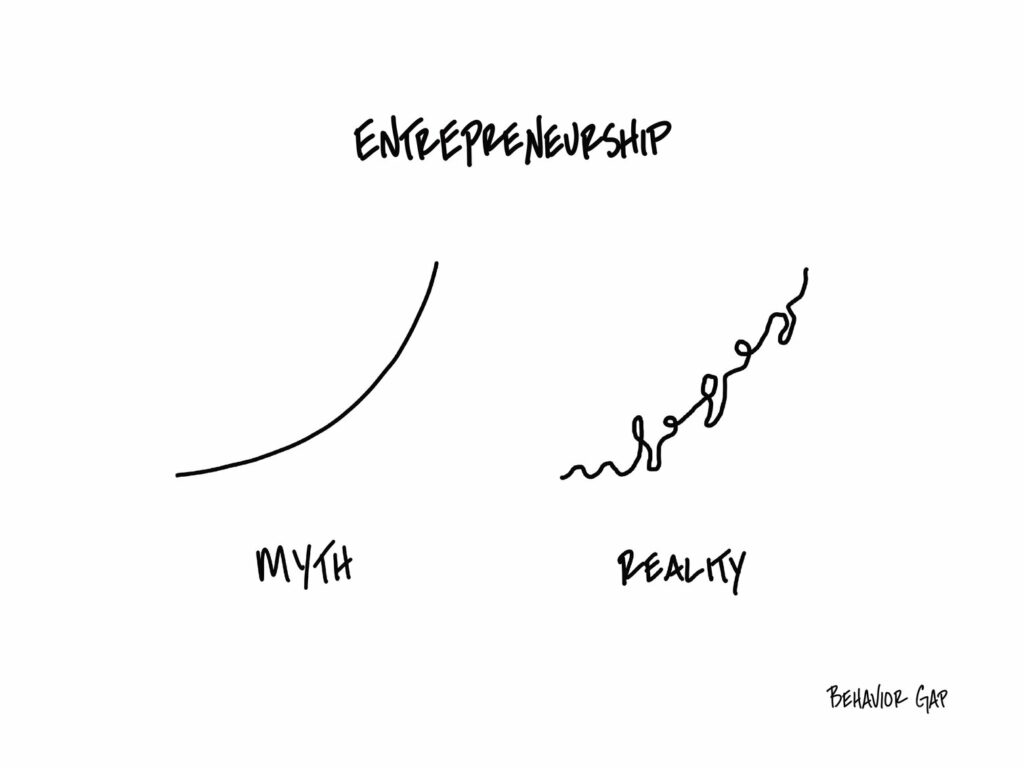

The funny thing about the way Bob tells the story is he doesn’t talk about the four times the business almost went bankrupt, the lucky breaks, or the hard work. Sure, he talks about #hustle and #crushingit… but according to Bob, the business’ growth was all up and to the right… like a hockey stick.

Cool story, right?

That’s the myth of entrepreneurship… Bob and the Hockey Stick.

The reality is that building a successful business is messy and unpredictable, and entrepreneurship is anything but linear.

You hit walls, challenges arise, people disappoint you. Things never go as planned. You have good breaks and bad breaks. Anyone who says there isn’t luck involved is a liar. There is no hockey stick. There’s only a squiggly, chaotic, unpredictable line between here and there.

-Carl

P.S. As always, if you want to use this sketch, you can buy it here.