Budgeting doesn’t have to be painful. In fact, it can be a fun game.

Some friends of mine played this fun little budgeting game I created called Carl Richards’ Budgeting Treasure Hunt.

When they started, they had a goal of saving $1 million dollars. Crazy, right? The only way that ever happens is by getting lucky in the stock market or an inheritance.

Years later, I got a call. “Carl,” they told me, “we did it! We just crossed the $1 million mark.”

They didn’t get lucky, and they didn’t inherit a ton of cash. They just played the game. Here are the rules.

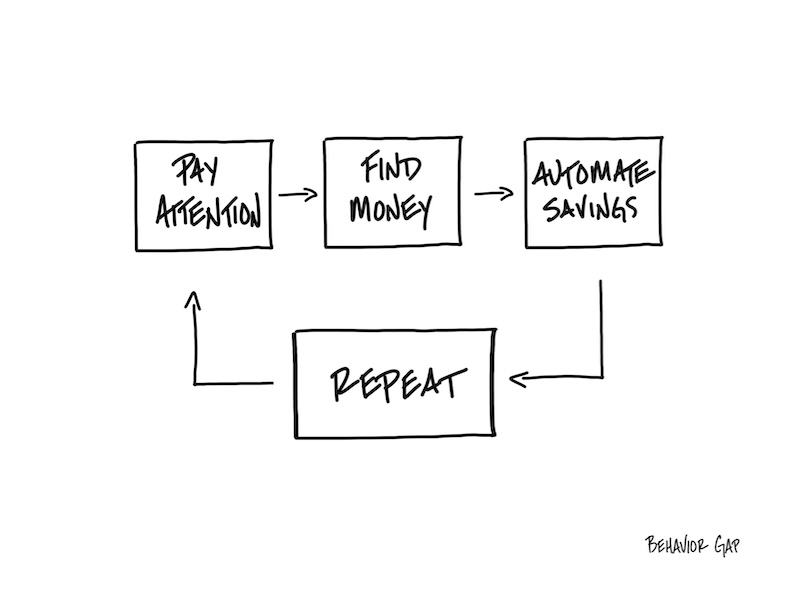

1- Pay attention. Every time you spend money, just take three seconds to notice what you’ve done. Don’t judge, just notice.

2- Find wasted money. If you start to notice that certain purchases don’t make you happy, consider that wasted money. Another good place to find wasted money is in basic utilities or subscriptions you’re no longer using.

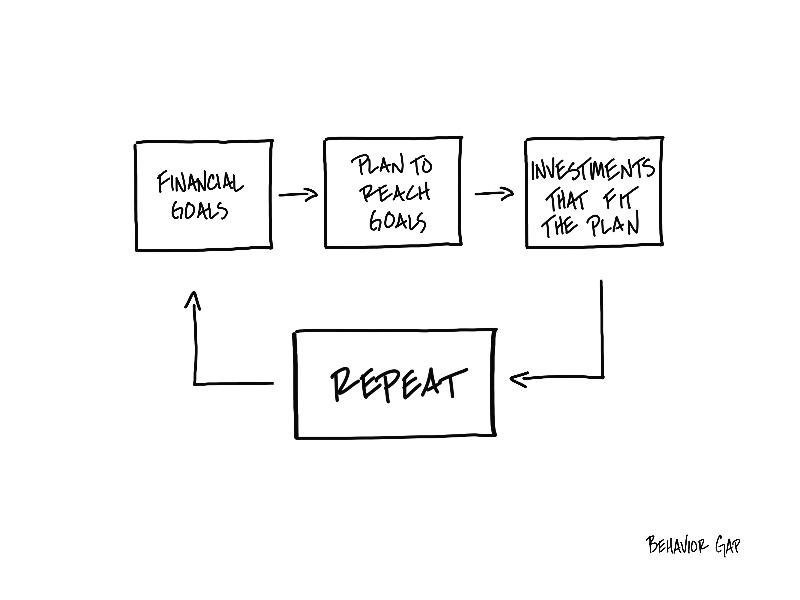

3- Automate savings. Take the wasted money you found and spend it! But the trick is, spend it by automatically saving it every month. This can go into a savings account, into an investment, or you can increase the amount you’re throwing at your mortgage.

4- Repeat. The goal is to see if you can move your automatic savings number up a little each month. This can actually be fun! Again, think of it as a game.

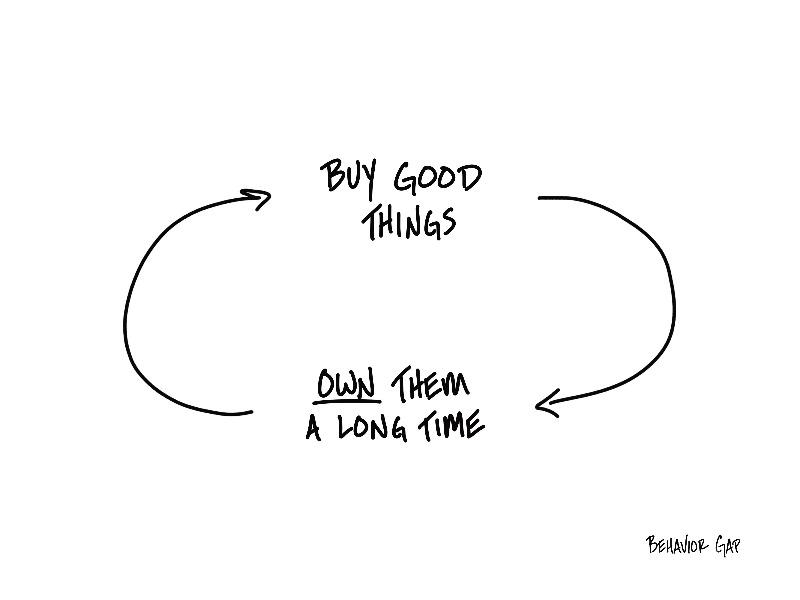

Meeting big financial goals is not about getting lucky or having a big break, it’s about consistently doing boring but effective things. The solution is not to grit your teeth and work harder at budgeting. The solution is a simple mindset shift from “Harder, Painful, Grrr” to “Fun, Exploration, Treasure Hunt.”

So stop trying so hard, and play the game.

-Carl

P.S. As always, if you want to use this sketch, you can buy it here.