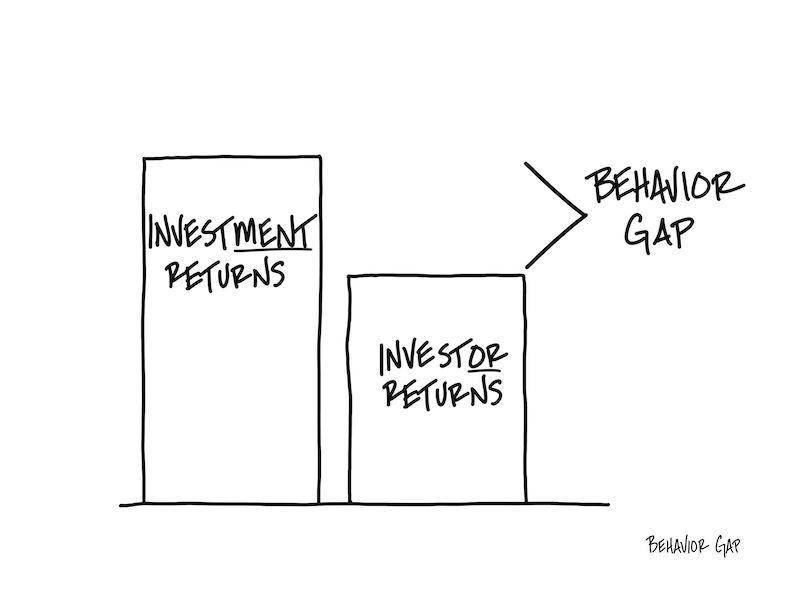

Investor behavior matters a lot. In fact, it probably matters more than skill. To understand why this is true, first you need to understand one fundamental concept: Investment returns and investor returns are almost always different.

In 1999, I was working diligently doing my job as an investment advisor or financial planner (I was never sure what to call myself back then). As far as I understood it, my job was to search for investments that would generate above-average returns for my clients. That’s what the entire industry was built on, and really, that’s what clients thought they hired me to do.

Above-average returns is called “alpha,” and finding even a little of it was worth any trouble. The search for alpha was why investment firms hired bright people and gave them bigger computers than the “other guys.” As I was searching for a little alpha anywhere I could find it, I ran across a little annual study done by Dalbar. This study attempts to find out how investors did compared to the average investment. You see, investment returns are not the same as investor returns.

Investment returns that you see in the paper or in marketing material are based on the assumption that you invest a lump sum at the beginning of the period, and then you leave it alone. You do not buy or sell. You do not change your mind and trade to another fund. You just buy once and hold.

Investor returns measure your real-life return. The return you earn as you buy and sell your investments, or switch from one investment to another in your search for the next hot thing (remember our search for alpha?).

Well, for as long as Dalbar has been doing their study, the result has been shocking! The latest update is not much different from the one I read back in 1999. The study uses the S&P 500 as a proxy for the “average investment.” For the 20-year period ending 2007, the average investment return was 11.81%. The average investor return was 4.48%.

Now think about this for a moment: The entire industry is based on the idea that their job is to find the best investments, and in the process, they are killing the patient. The well-intentioned search for alpha is resulting in the average real-life person underperforming the S&P 500 by over 7%. That is crazy stuff.

When I realized the implications, my entire job changed. I realized that investment success is not about skill — it is about behavior. I could not figure out why this story was not being told anywhere. I even remember reading an issue of Consumer Reports that went into great detail about how to save a percent on fees by buying no-load mutual funds. Then, buried in the article was one sentence that mentioned the Dalbar study and warned people about this 7% problem.

Three pages devoted to saving a percent, one sentence that mentioned a massive problem but offered no ideas for solving it! I started telling the story everywhere I could. I drew this sketch on the whiteboard in every client meeting and at every public speaking engagement.

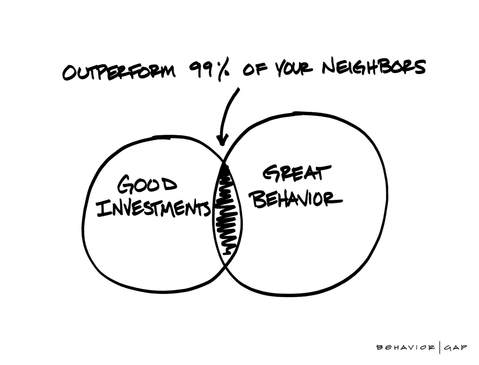

It turns out my job was not to find great investments, but to help create great investors. If all you had to do was buy good (versus great) investments and then behave correctly, that changes everything. I decided that the search for alpha didn’t matter (turns out it’s a fool’s errand anyway, but I didn’t know that at the time) if you lost 7% in the process just because of bad behavior. I decided to leave the complex task of finding the best investment to the smart guys with the big computers; I was going to focus on the simple problem of helping people behave correctly.

It turns out that outperforming your neighbor is not about finding better investments, it is about behaving better. Wow, if this is true, think of what it does to your life. No more Jim Cramer, no more late nights after work trying to find the next Microsoft.

If this is true (year after year, studies tell the same story), then the focus is really on the few things that you control.

If this is true, your relationship with a financial planner should be based on trust.

If this is true, we can focus on the simple, but not easy, task of becoming a better investor.

The lesson is that investment success isn’t about skill. It’s about behavior.

. . .