How do we know that what we think is what we really think, and not just what someone else wants us to think? Let that thought percolate for a minute.

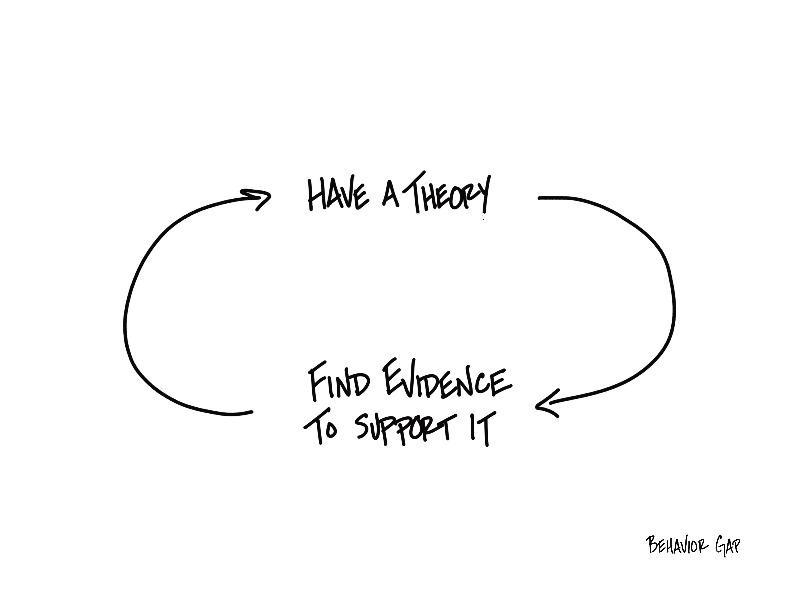

It turns out that it doesn’t take much to make us think something we didn’t previously. Our minds are biased to work against us. It’s often referred to as “confirmation bias.”

It almost seems like a magic trick, but it’s really our brains searching for a way to end uncertainty. There are so many things we don’t know. Sometimes the knowledge just isn’t available yet. But many times, we’re looking for a shortcut.

If we can find some evidence that supports our theory, we can stop thinking about it. For instance, there are plenty of people trying to sell investors on “guaranteed” stock-picking strategies. They sound great in theory. To make them look even more attractive, the inventors of these strategies present evidence that makes them look like can’t-lose propositions.

Oddly enough, the evidence is usually cherry-picked. We rationalize their story, telling ourselves we can ignore the supposed outliers and that it really does work — most of the time. As a result, we latch on to the good stuff and run with it. We barely stop to think before signing up to learn more about their amazing stock-picking strategy, all for three easy payments of $39.99. After all, it’s guaranteed.

It happens in smaller ways, too. We tell ourselves we can’t possibly save money every month. To back up this theory, we look only at the total left in the checkbook on the last day of the month. Clearly, we can’t save more. But in the process, we skip over all the line entries for unplanned purchases of things that easily fall into the “want” category. Of course, it doesn’t matter. We’ve already “confirmed” our theory. We have no more money to save.

Ultimately, confirmation bias is about telling ourselves a really good story. I don’t blame people at all for preferring the story they’ve managed to tell themselves. But if we’re at all serious about making smarter decisions, we need to practice storytelling less and playing devil’s advocate more.

Because, as the old saying goes, the truth will set us free. Of course, we may very well discover our theory is correct, but it’s just as likely that we’ll discover our theory has some holes in it.

Confirmation bias is super hard to deal with, and it is critical that we are at least aware of our own tendency to fall prey to it.

. . .