Once upon a time, I sent an email to my newsletter subscribers with a simple question: Is it hard for you to talk about money with your spouse or partner?

Most people said yes, but the response I got that really hurt was this:

“YES! It is hard, because it often feels defensive. She spent too much. He spent too much. Was that aligned with our values? What are our values? How come there isn’t more? And if only she would spend less, then I wouldn’t have to work so hard. :)”

If that sounds too close to home, imagine how it felt to see those words from… you guessed it… my wife!

I have to admit that upon reading that, I was discouraged. There was even a part of me that felt like a fraud. Who am I to be talking to other people about money if my own wife feels this way?

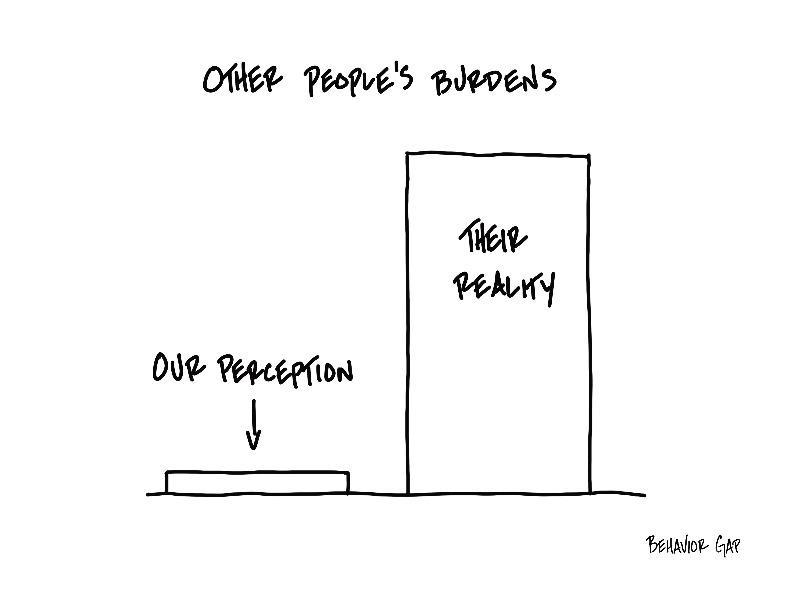

But I also need to admit she’s right. It’s challenging for us to talk about money. Not just with each other, but with our parents, our children, even our siblings, and friends.

And you know what? That’s OK.

This, my friends, is one of the keys to talking about money: knowing that it’s going to be hard. Sometimes, it’s going to be painful. And that’s OK.

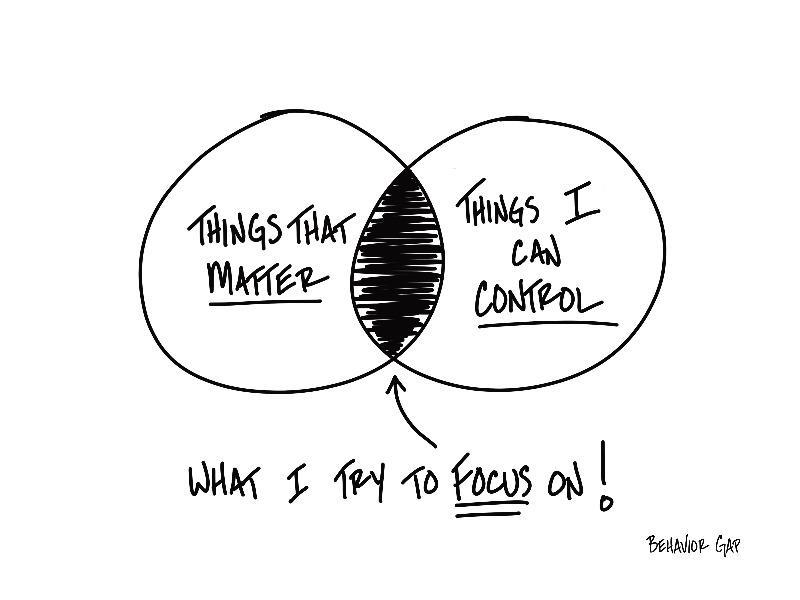

Talking about money may not be necessary for all couples. But for the vast majority, it’s like taking out the trash or doing the laundry—just one of those things that has to happen.

So do your best, keep it as civil as possible, and maybe even think of it as an opportunity to connect more deeply. And, like anything else difficult in life, if at first you don’t succeed, try and try again.

-Carl

P.S. As always, if you want to use this sketch, you can buy it here.