If you really want to crush it, you need to rest.

Seems obvious, but for me, it’s a very painful lesson I am still trying to learn.

You know the gig: up at five in the morning, daily workouts, paleo, bulletproof, gluten-free, cold showers.

Check, check, check.

Build a business, start a side hustle, and dominate social media. Yeah, all that too.

It feels like we live in the “Crush It Age.” Every time you turn around, somebody is crushing something. Working faster. Trying harder. Getting smarter. Putting in longer hours. Sleeping less.

Sheesh… no wonder we’re so tired!

Now listen, I’m all for hard work. That’s not my problem, and I don’t think it’s your problem either.

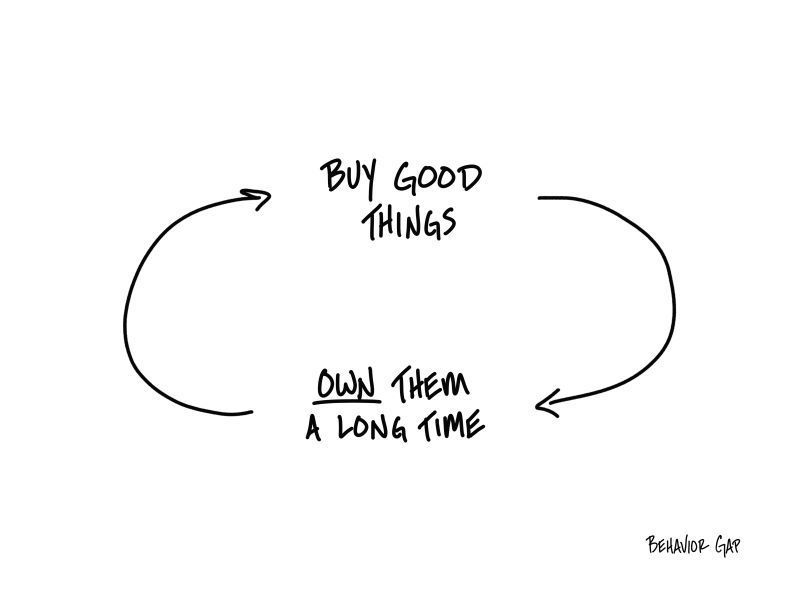

The point I’m trying to make here is that you can only work hard without rest for so long before you end up a broken human.

Trust me, I know.

But it’s not just me telling you, this is settled doctrine at this point.

It’s much better to “work hard, rest, work hard, rest” than to “work hard, work hard, work hard, crash.”

-Carl

P.S. As always, if you want to use this sketch, you can buy it here.