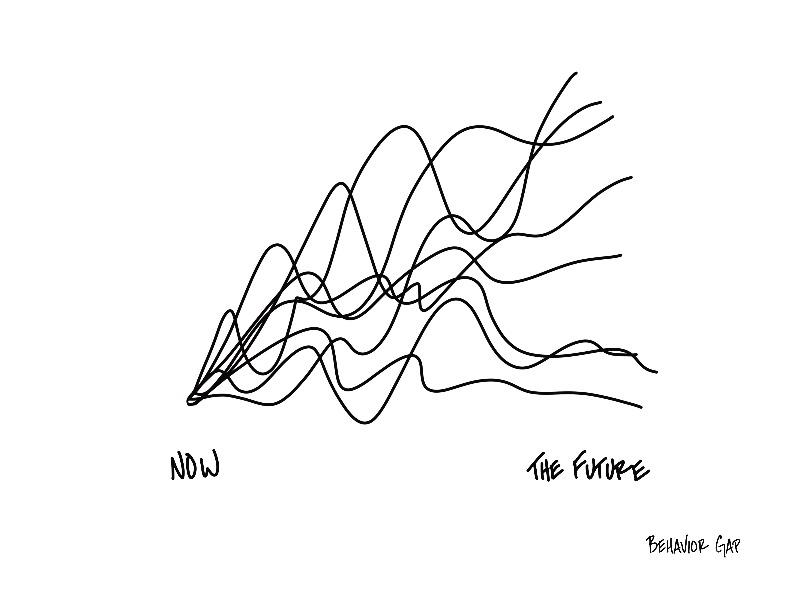

Repeat after me: You. Can’t. Time. The. Stock. Market.

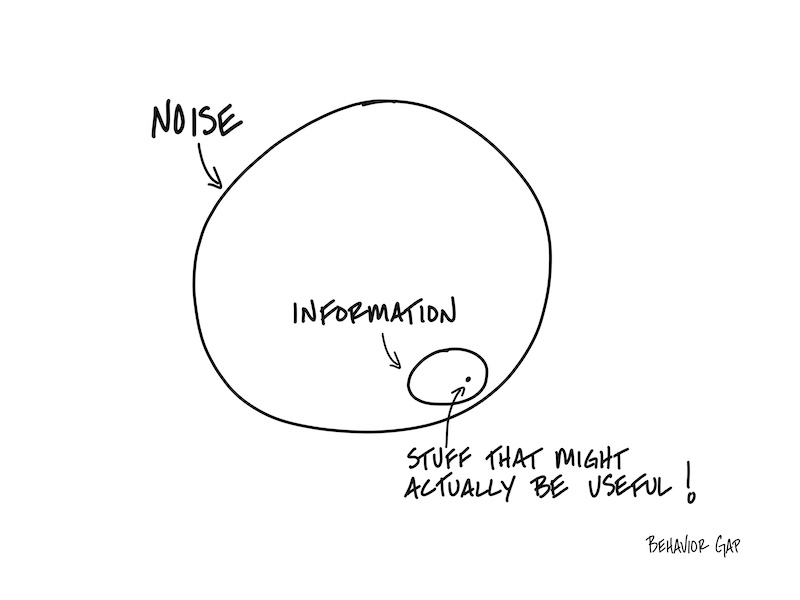

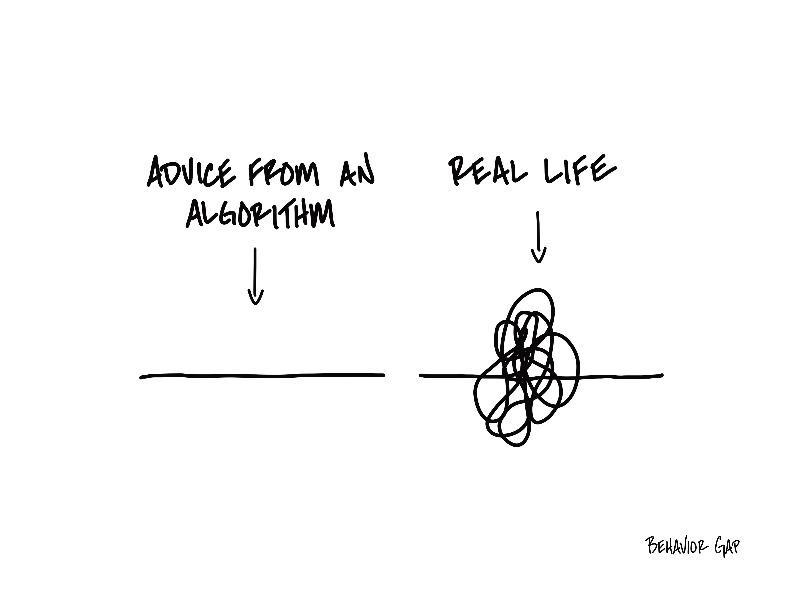

Sure, there are data models that may be 93.7% accurate 91.8% of the time. But there’s no such thing as a stock market oracle or crystal ball.

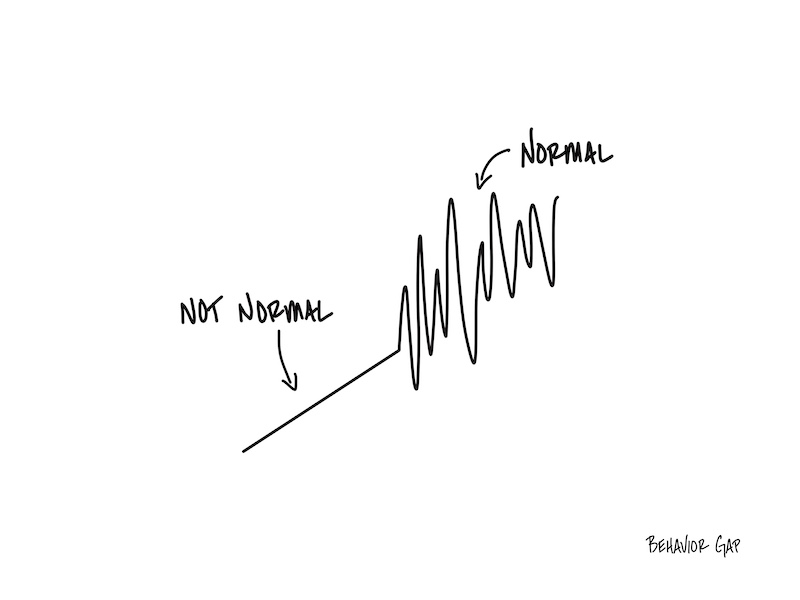

The stock market is not like gravity or even the weather. It doesn’t follow set laws.

On any given day, the stock market represents the collective feelings of all of us. More often than not, those feelings are based on emotions (rational or not). And it is only in hindsight that we recognize our mistakes.

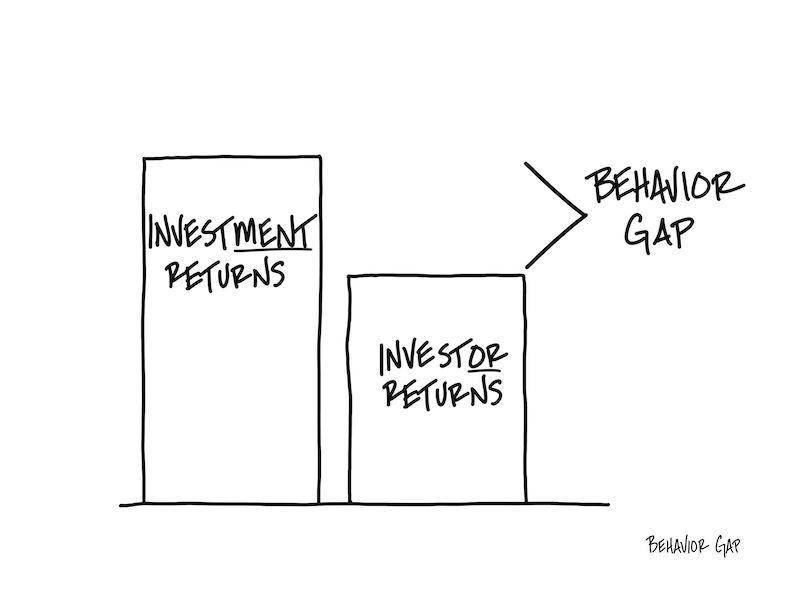

So while on one level, human behavior seems predictable (e.g., we get excited and buy stocks when they are flying high; we get scared and sell when stocks decline), it’s awfully hard to know what we’re doing until it’s too late.

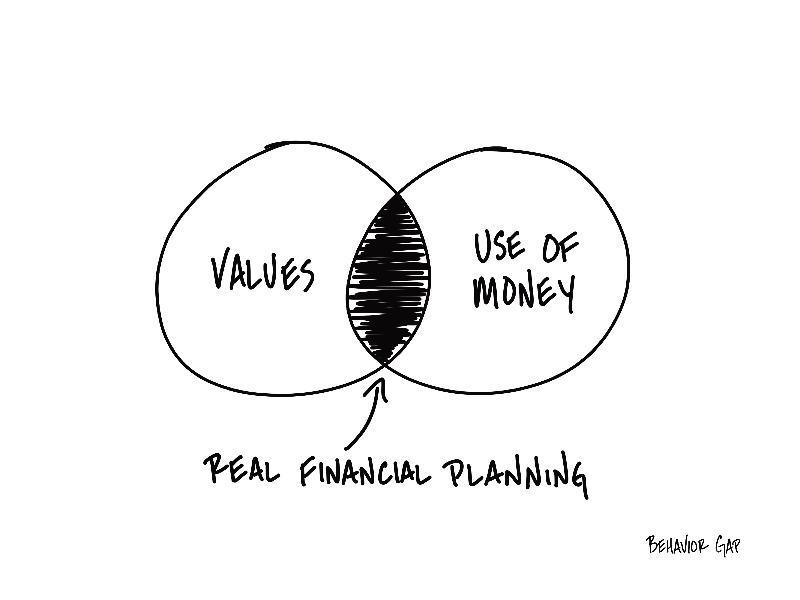

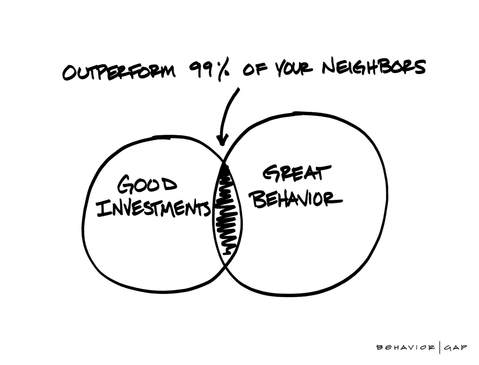

The basic facts have remained the same. Over time (think 10, 15, or 20 years), stocks typically do better than bonds, and bonds typically do better than cash. Low expenses are typically a good sign of future relative performance. We also know that a diversified portfolio will help protect you from the variability of the stock market. Typically.

Beyond that, stock market timing is just a guessing game, and we’re pretending to know something we don’t.

I’m ready to stop pretending. Are you?

-Carl

P.S. As always, if you want to use this sketch, you can buy it here.